BELFIELD 1945-56. (2)

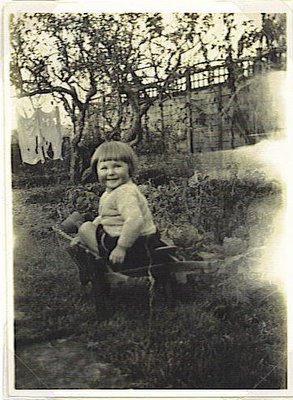

In October 1946 my father spent £5.0.11 on large trumpet daffodils, tulips and winter aconites for the garden. My mother, a keen and knowledgeable gardener, took great delight in restoring the neglected garden. She grew many plants from seed in the Conservatory, where the wooden shelving running along the length of its wooded side, made for her seedling trays, was still there when the house was for sale in 2002. My father used to tackle the heavy work - clearing brambles, pruning etc.

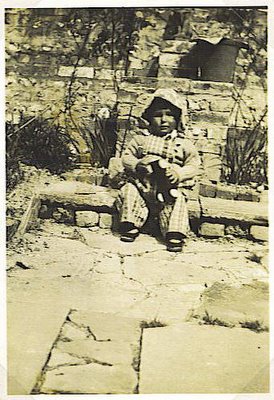

Near the conservatory was a stoned paved path and some shallow steps leading into a thicket of overgrown bushes and dense undergrowth. Upon clearing a way through, my parents were excited to discover a paved area within - the remains of an arbour which they reinstated.

Mr & Mrs W-----

To cope with grass cutting and the vegetable garden they employed a gardener, a retired quarryman from Portland called Mr W-----, who lived with his wife in the main street in Fortuneswell. Mrs W-----, who was extremely deaf, was a big strong woman, twice the size of her husband. She was employed to clean Belfield, but only came when we were back in London, and we would return to find everything spotlessly clean and shining.

Unfortunately she did not know her own strength, and occasionally things got damaged or broken. Dusters would be reduced to cobweb-like thinness after only a few washes, and rugs were liable to skid on her highly polished floors the moment one stepped on them. When we were there for the long summer holiday, she and Mr W----- would be invited to tea one afternoon and she would gloomily look around and remark on how dirty the house was!

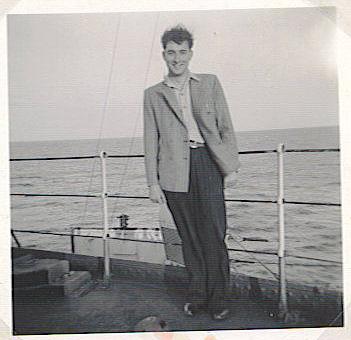

Lionel W-----

The W-----s had a son called Lionel who was in the Fleet Air Arm and was the apple of his mother's eye. She presented us with a framed photograph of him in his uniform, which we would have to remember to put out in a prominent place when we knew she was coming or on our return to London.

Mrs W----- was an ardent royalist, until the day when the newly crowned Queen was driven past our house on a visit to Portland. Mrs W----- was there with her Union Flag, hanging out of her window and waving enthusiastically as the motorcade drove past. But, alas, the Queen failed to return Mrs W-----'s wave. At the critical moment, she was busy waving to the other side of the street. Mrs W----- took it as a personal insult and never forgave her.

With Mrs W----- at Belfield

Before the discovery of Mrs W-----, for a very short time, my mother had tried employing a cleaner who had recently been a patient at Herrison, then a psychiatric hospital near Dorchester. I do not remember her name, only that she seemed to be rather distrait and vague. After she left, I was told that she had "been let out of Herrison" but had to return there for further treatment. It sounded ominous and a bit sinister, and for a long time I thought that "Herrison" was some sort of limbo place, akin to Purgatory.

Odd too was a plumber who came to the house to do some work, went home at the end of the day promising to return the following morning to complete the job, but never came back. Several years later he suddenly re-appeared one day to finish the work he had long abandoned, and was surprised and taken aback to be told that in the meantime another plumber had been employed to finish it. His excuse was that when he woke up the next day, he had felt unable to get out of bed to go to work, so his wife had encouraged him to stay where he was until he felt better and he had done just that.

Work on the external renovation of the house began in September 1946 when my parents received a quote from Rendell and Son of Weymouth. For repairs and outside painting of wood and iron work to the house, conservatory and verandah, the price quoted was £135.12s and for the re-painting of stone and stucco work: £117.2s plus a further £10 for sundry repairs. Three years later, the exterior had to painted again; perhaps the quality of post-war paint was not very good. This time the contractor was F. Selby and Sons, whose quote was only £67.17.6.

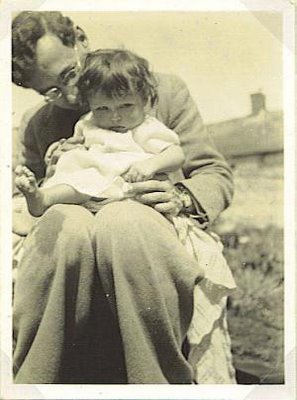

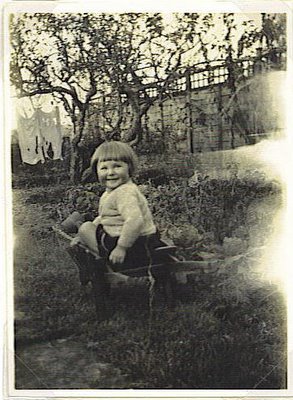

Mr W-----, my mother, father and me.

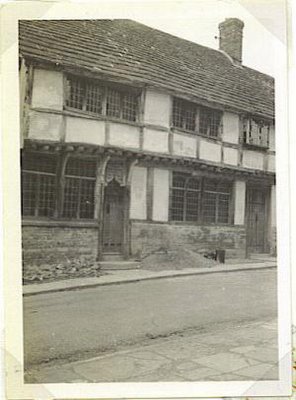

After Grandpa Squibb died on June 10th 1946, a lot of his furniture and possessions came to Belfield. My parents had already started buying furniture for the house, mainly from two Dorchester antique dealers. Some from Mr Pitman, but mostly from Mr Legg who owned a shop at the bottom of High Street East which is still there, run now by his son Michael.

This was a good time to be buying antiques, as post-war prices were rock bottom, and my mother was particularly interested in Regency furniture which was not yet fashionable, so there were some good bargains to be had. She learnt a lot from Mr Legg, and I too was taught by him how to detect genuine old from reproduction furniture by running my fingers along the edges underneath tables and chairs. If they felt sharp, it was likely to be new.

To reveal the true colours of a dirty oil painting, he would lick his finger and rub it over the surface, but this landed me in trouble one day when I tried it out in an art gallery I was visiting with my parents.

I had gone on ahead a little way, and was looking at a large and very dark landscape which featured some cows by a river. Being curious to see how it might look if cleaned, I went up to it and did just what I thought Mr Legg would have done.

There was a squawk of outrage from a nearby attendant, who rushed over and frantically and indignantly wiped the place I had violated with his handkerchief. My parents, although secretly amused by the incident, were full of apologies, and after insisting that I meant no harm, we hurriedly left the gallery in deep disgrace!

<< Previous post · First post · Next post >>

Near the conservatory was a stoned paved path and some shallow steps leading into a thicket of overgrown bushes and dense undergrowth. Upon clearing a way through, my parents were excited to discover a paved area within - the remains of an arbour which they reinstated.

To cope with grass cutting and the vegetable garden they employed a gardener, a retired quarryman from Portland called Mr W-----, who lived with his wife in the main street in Fortuneswell. Mrs W-----, who was extremely deaf, was a big strong woman, twice the size of her husband. She was employed to clean Belfield, but only came when we were back in London, and we would return to find everything spotlessly clean and shining.

Unfortunately she did not know her own strength, and occasionally things got damaged or broken. Dusters would be reduced to cobweb-like thinness after only a few washes, and rugs were liable to skid on her highly polished floors the moment one stepped on them. When we were there for the long summer holiday, she and Mr W----- would be invited to tea one afternoon and she would gloomily look around and remark on how dirty the house was!

The W-----s had a son called Lionel who was in the Fleet Air Arm and was the apple of his mother's eye. She presented us with a framed photograph of him in his uniform, which we would have to remember to put out in a prominent place when we knew she was coming or on our return to London.

Mrs W----- was an ardent royalist, until the day when the newly crowned Queen was driven past our house on a visit to Portland. Mrs W----- was there with her Union Flag, hanging out of her window and waving enthusiastically as the motorcade drove past. But, alas, the Queen failed to return Mrs W-----'s wave. At the critical moment, she was busy waving to the other side of the street. Mrs W----- took it as a personal insult and never forgave her.

Before the discovery of Mrs W-----, for a very short time, my mother had tried employing a cleaner who had recently been a patient at Herrison, then a psychiatric hospital near Dorchester. I do not remember her name, only that she seemed to be rather distrait and vague. After she left, I was told that she had "been let out of Herrison" but had to return there for further treatment. It sounded ominous and a bit sinister, and for a long time I thought that "Herrison" was some sort of limbo place, akin to Purgatory.

Odd too was a plumber who came to the house to do some work, went home at the end of the day promising to return the following morning to complete the job, but never came back. Several years later he suddenly re-appeared one day to finish the work he had long abandoned, and was surprised and taken aback to be told that in the meantime another plumber had been employed to finish it. His excuse was that when he woke up the next day, he had felt unable to get out of bed to go to work, so his wife had encouraged him to stay where he was until he felt better and he had done just that.

Work on the external renovation of the house began in September 1946 when my parents received a quote from Rendell and Son of Weymouth. For repairs and outside painting of wood and iron work to the house, conservatory and verandah, the price quoted was £135.12s and for the re-painting of stone and stucco work: £117.2s plus a further £10 for sundry repairs. Three years later, the exterior had to painted again; perhaps the quality of post-war paint was not very good. This time the contractor was F. Selby and Sons, whose quote was only £67.17.6.

After Grandpa Squibb died on June 10th 1946, a lot of his furniture and possessions came to Belfield. My parents had already started buying furniture for the house, mainly from two Dorchester antique dealers. Some from Mr Pitman, but mostly from Mr Legg who owned a shop at the bottom of High Street East which is still there, run now by his son Michael.

This was a good time to be buying antiques, as post-war prices were rock bottom, and my mother was particularly interested in Regency furniture which was not yet fashionable, so there were some good bargains to be had. She learnt a lot from Mr Legg, and I too was taught by him how to detect genuine old from reproduction furniture by running my fingers along the edges underneath tables and chairs. If they felt sharp, it was likely to be new.

To reveal the true colours of a dirty oil painting, he would lick his finger and rub it over the surface, but this landed me in trouble one day when I tried it out in an art gallery I was visiting with my parents.

I had gone on ahead a little way, and was looking at a large and very dark landscape which featured some cows by a river. Being curious to see how it might look if cleaned, I went up to it and did just what I thought Mr Legg would have done.

There was a squawk of outrage from a nearby attendant, who rushed over and frantically and indignantly wiped the place I had violated with his handkerchief. My parents, although secretly amused by the incident, were full of apologies, and after insisting that I meant no harm, we hurriedly left the gallery in deep disgrace!

<< Previous post · First post · Next post >>