CERNE ABBAS 1940-1945. (6)

Meanwhile, the invasion of France continued: my mother could hear the bombardment as far away as Cerne. In his letter of June 18th 1944, my father wrote:

In Cerne the previous Friday night:

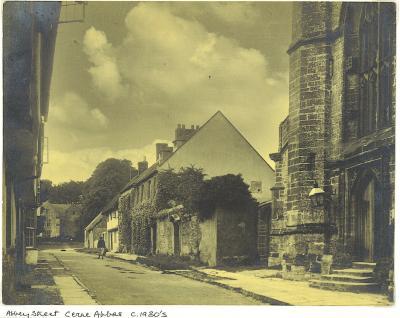

Until recently the replacement window still had different sized panes of glass and glazing bars from those on the right hand side of the door: the window was not fully restored until after it had again been smashed, this time during a night-time raid when the Post Office safe was thrown through it. This happened just as Cerne was about to celebrate the 50th anniversary of V.E. Day.

By August, 80% of the flying bombs which came over were being destroyed, but on September 8th the first rockets reached London. My father never talked to me about his part in the War and life in London at that time. When I was little he used to entertain me by imitating the sound of a doodlebug, but that was all.

Transport at that time cannot have been easy, but my father continued travelling all over the country by train in order to appear in court in such towns as Nottingham, Sheffield, Cambridge and Watford. And of course there was the weekly commute between London and Cerne. He described his journeys from Cerne to catch the train back to London from Dorchester in a letter to his father in November 1944:

Because of his poor eyesight he never learnt to drive a car, and neither did my mother.

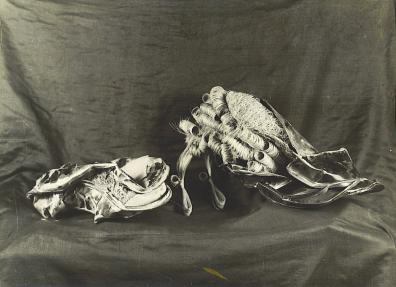

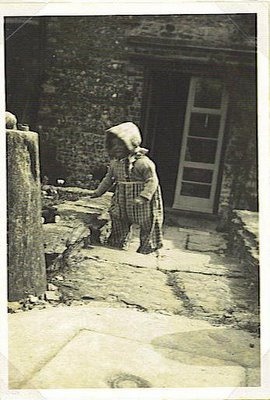

My personal memories of that time are mostly trouble-free. I remember falling into the stream which runs down Abbey Street from the duck pond, and meeting Minkey Patterson, who lived opposite, as I climbed out. She told me that my mother was looking for me along the mill-stream path, so I must have escaped from her watchful eye and run on ahead, while she feared that an accident had befallen me. I remember too, being pushed along by the mill-stream in my push chair one afternoon and seeing a horse and rider on the opposite bank.

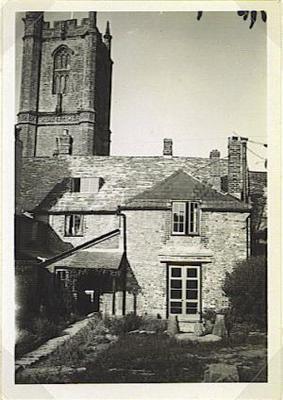

Celandines used to grow in profusion on the bank just inside the gate to the burial ground when the path up to Belvoir was line with yew trees (felled in the 1960's when they became diseased). I have lots of early memories of flowers: primroses in the hedgerows, as there still are, and nasturtiums and "Chinese Lanterns" in the Pitchmarket garden.

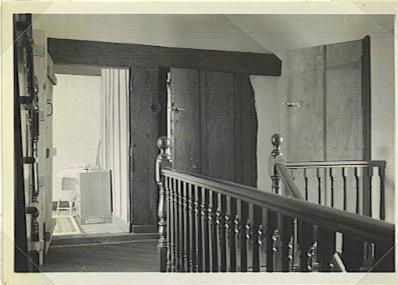

One event which is not mentioned in any of the letters to my grandfather is the "privy" I made out of a hat box in my bedroom, and used! I was fascinated by the outside privy at Kay and Nurses' cottage and wanted one of my own!

<< Previous post · First post · Next post >>

"These new pilotless planes gave me a sleepless night on Thursday, which was my night on duty. The "alert" went at 11.30 and we did not get the "all clear" until 9.30 the next morning - the longest raid since the winter of 1940-41. Nothing seemed to be happening in the middle of London, and we only heard the gun-fire at long intervals, but still being on duty I had to be awake all the time. I think they are going to be more of a nuisance than anything else. Indeed, it does not seem that they can be an effective weapon of war."

In Cerne the previous Friday night:

"We heard a great crash just before we went to bed and found that an American lorry had backed into the windows of the paper shop" [now the Post Office]. "It not only broke the glass but the wood-work as well. The sound of the glass being swept up reminded me of the morning after an air-raid."

Until recently the replacement window still had different sized panes of glass and glazing bars from those on the right hand side of the door: the window was not fully restored until after it had again been smashed, this time during a night-time raid when the Post Office safe was thrown through it. This happened just as Cerne was about to celebrate the 50th anniversary of V.E. Day.

By August, 80% of the flying bombs which came over were being destroyed, but on September 8th the first rockets reached London. My father never talked to me about his part in the War and life in London at that time. When I was little he used to entertain me by imitating the sound of a doodlebug, but that was all.

Transport at that time cannot have been easy, but my father continued travelling all over the country by train in order to appear in court in such towns as Nottingham, Sheffield, Cambridge and Watford. And of course there was the weekly commute between London and Cerne. He described his journeys from Cerne to catch the train back to London from Dorchester in a letter to his father in November 1944:

"I have no difficulty about getting a car in Cerne and I always have one if it is wet, cold or dark. When I do ride [his bicycle] I always have a waterproof cape, leggings and sou'wester in the bag at the back in case it comes to rain on the way. When the weather is decent I enjoy the ride but do not set out if it is not fine. During the school term there is a bus which leaves Cerne at 8.30 and I travel on that very often and have a car to meet me on Friday."

Because of his poor eyesight he never learnt to drive a car, and neither did my mother.

My personal memories of that time are mostly trouble-free. I remember falling into the stream which runs down Abbey Street from the duck pond, and meeting Minkey Patterson, who lived opposite, as I climbed out. She told me that my mother was looking for me along the mill-stream path, so I must have escaped from her watchful eye and run on ahead, while she feared that an accident had befallen me. I remember too, being pushed along by the mill-stream in my push chair one afternoon and seeing a horse and rider on the opposite bank.

Celandines used to grow in profusion on the bank just inside the gate to the burial ground when the path up to Belvoir was line with yew trees (felled in the 1960's when they became diseased). I have lots of early memories of flowers: primroses in the hedgerows, as there still are, and nasturtiums and "Chinese Lanterns" in the Pitchmarket garden.

One event which is not mentioned in any of the letters to my grandfather is the "privy" I made out of a hat box in my bedroom, and used! I was fascinated by the outside privy at Kay and Nurses' cottage and wanted one of my own!

<< Previous post · First post · Next post >>